SAN FRANCISCO--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Voce Capital Management LLC (“Voce”) is the beneficial owner of more than 1.3 million shares of OnDeck Capital, Inc. (NYSE: ONDK) (“OnDeck” or the “Company”), making Voce one of the Company’s largest stockholders. Today, Voce announced that it is planning to vote all of its shares AGAINST the reelection of the three “Class III” Directors at the May 7, 2020 Annual Meeting of Stockholders (the “Annual Meeting,”) and is strongly urging its fellow stockholders to do so as well.

Voce issued the following letter to OnDeck stockholders in connection with the announcement:

April 17, 2020

Dear Fellow Stockholders of OnDeck Capital, Inc.:

Voce Capital Management LLC (“Voce”) is the beneficial owner of more than 1.3 million shares of OnDeck Capital, Inc. (NYSE: ONDK) (“OnDeck” or the “Company”), making us one of the Company’s largest stockholders.

As investors in OnDeck for the past year, we’ve actively and regularly engaged with management, consistently providing recommendations for how OnDeck could improve stockholder value. Those discussions have intensified in recent weeks and, at our request, have broadened to include dialogue with several members of OnDeck’s Board of Directors (the “Board”). We have appreciated the professional and constructive tenor of these interactions.

But soothing words alone are not enough, particularly for a company with issues as urgent, and chronic, as OnDeck’s. Stockholders have suffered from years of strategic drift and expense profligacy, resulting in the loss of 93% of the stock’s value since its IPO just over five years ago. As far back as August of 2019, we urged management to tighten its focus and enhance profitability:

“We believe OnDeck’s core value proposition is strong, but significant work needs to be done to reestablish credibility with investors. OnDeck is clearly stuck in the ‘dugout’ at the present time. A series of disappointments and surprises has left investors ‘dazed and confused.’ Too many new initiatives, shifting priorities and mixed signals [have left] investors uncertain whether OnDeck’s opportunity set is growing or shrinking.”1

We fully appreciate the challenges that the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic poses to OnDeck, and many other companies that we own, and have been mindful of them in our dealings with the Company. Yet OnDeck’s slow response to current events has only magnified the issues that now confront it. We met with management over a month ago as the crisis erupted, and pleaded with them to initiate immediate expense reductions in order to protect the Company’s ability to continue to serve its core customer base of small US businesses; yet so far, no action has been taken, further imperiling the Company.

We also believe that OnDeck’s weak corporate governance has enabled and prolonged these long-running problems, and that lasting progress cannot be made until this issue is addressed. However, out of further sensitivity to the operating environment, we committed that we would fully support the Board at this year’s Annual Meeting if it took only one step: include and recommend a proposal to de-stagger the Board immediately so that all Directors would be subject to reelection every year, starting at the 2021 Annual Meeting, thereby deferring some of these issues for a year while preserving stockholders’ ability to hold the Board accountable for its performance. We viewed this proposal as measured and proportional, taking all things into account.

Incredibly, the Board refused.

In light of this most recent example of the Company’s failure to align what it does with what it says, we felt we could not simply stand idly by for another year. At a certain point, even a health crisis like the current one cannot be used to shield a Board from any accountability or responsibility. We therefore intend to vote all of our shares AGAINST the reelection of the three “Class III” Directors at the May 7, 2020 Annual Meeting of Stockholders (the “Annual Meeting”) and are strongly urging our fellow stockholders to do so as well.

Batter, batter, what’s the matter?

OnDeck’s problems began long before the tragic and unforeseeable global pandemic erupted.2 It debuted in a splashy December 2014 IPO, with a $1.3 billion initial valuation, that seemed to validate the hopes and dreams of the venture capitalists that had funded and promoted OnDeck as a fin-tech unicorn.

But it never worked out that way, at least not for OnDeck’s public investors. In less than two years, OnDeck plunged from $20 per share to $4. In six calendar years as a public company, it has had only two years with positive returns for stockholders, one of which was negligible. The stock’s losses during this time were staggering and consistent:

OnDeck Annual Returns |

||

Year |

Price |

1Yr Return |

2015 |

$10.30 |

(54.1%) |

2016 |

$4.63 |

(55.0%) |

2017 |

$5.74 |

24.0% |

2018 |

$5.90 |

2.8% |

2019 |

$4.14 |

(29.8%) |

2020 YTD |

$1.35 |

(67.4%) |

Other than a brief period when the stock responded favorably to expense reductions forced by public pressure from another dissatisfied stockholder, OnDeck has languished around that price (the VWAP from 1/1/17 through 2/21/20 was $5.25). In 2019, when the Russell 2000 leapt 25%, and OnDeck’s peers returned 18%, OnDeck fell 30%.3 The total return of its stock since going public makes it one of the worst performing IPOs of its generation.

| OnDeck TSR Since IPO | ||

| Through | Price | Return |

| 12/31/19 | $4.14 |

(79.3%) |

| 4/15/20 | $1.35 |

(93.3%) |

While COVID-19 has clearly amplified OnDeck’s challenges, even during this period OnDeck has underperformed its peers. Year-to-date, OnDeck is down 67%, compared to peers down 52% during this time. At its lows in March, it had lost more than 80% of its value just since the onset of the virus panic on February 24. Now a penny stock – it actually has closed below $1.00 per share several times recently, trading like an option rather than a stock – its market capitalization (well less than $100 million) and technical profile further confirm Wall Street’s lack of respect for the stock, if not the Company. It also illustrates just how difficult it will be for OnDeck to recover unless radical and urgent action is taken now.

The boo-birds are out

Underpinning the collapse of OnDeck’s stock has also been the implosion of its valuation, reflecting investors’ increasing loss of faith, and sheer frustration, with its performance and direction.

Despite the top-line growth and the maturity of its business model, OnDeck has proven increasingly unable to forecast results or manage investor expectations. In the past five quarters (4Q18-4Q19), OnDeck met or exceeded both its revenue and adjusted net income guidance just three times, and fulfilled market expectations on those metrics just twice. In four of those five quarters, it badly whiffed on one or both measures or disappointed the market with its guidance. The immediate (one-day) stock price reactions to these earnings reports tell us everything we need to know: The stock fell in four out of the five periods (with three double-digit drops).

OnDeck’s inability to deliver consistent results has kept all but the most courageous of analysts in the bullpen. Only two out of more than ten covering firms have the stomach to recommend the stock. For most, OnDeck is a perpetual “wait and see” story and most don’t seem to follow the Company closely or to even care much; below is a representative excerpt from a Stephens report on 2/12/20:

“2020 Another Wait and See Year . . . 2019 closed out the year with a 41% y/y decline to EPS. While 2020 may be better, it still doesn’t return OnDeck to 2018 levels, and we do not see any particular 2020 catalysts. Achieving 2020 guidance would send the stock higher, but there has been enough volatility in execution . . . to discount guidance until it is achieved.”4

Over the prior year (from 12/31/18 until 2/21/20), OnDeck’s multiple of Price to Book Value (“P/BV”) shriveled from 1.6x to 0.9x. This compares to an average P/BV of its peers of 1.3x, which stayed constant during that time. If earnings were reliable enough to drive valuation, we would have likely seen an even more dramatic compression of its P/E multiple. Rolling forward to today, OnDeck’s P/BV is now 0.3x, meaning that investors have so little confidence they believe the Company’s assets are worth only thirty cents on the dollar. As we discuss in the next section, OnDeck’s expense load is so high that small swings in credit performance drive significant losses, making the market fully unable to trust its book value – hence the massive haircut.

No runs, no hits . . . lots of errors

The reasons for OnDeck’s many strike-outs over the years aren’t hard to identify, starting with its lack of cost discipline. In recent years, OnDeck’s expenses have grown much more rapidly than its revenues, rarely a great line-up for success.5 From 2017-19, OnDeck’s total revenues grew at a CAGR of 12.6%, yet its core operating expenses (technology and analytics; processing and servicing and G&A) swelled 17.2% percent per year during this time, adding $42 million of expense unrelated to sales and marketing over the two years.6 These operating expenses in total as a percent of revenue – a key efficiency ratio – surged from 32.4% in 2017 to 35.1% in 2019. Negative operating leverage, in the context of meaningful revenue growth and decent scale (almost $450 million in revenue), suggests disorder. It’s also at odds with the commitments management repeatedly made to stockholders. “We are also intensely focused on driving operating leverage,” promised Chairman and CEO Noah Breslow in May 2017 (1Q17 earnings call), and many other times, but it obviously hasn’t happened.7

$ in millions |

|

2017 |

|

2018 |

|

2019 |

|

2-Yr CAGR

|

Total Revenue |

|

$350 |

|

$398 |

|

$444 |

|

12.6% |

Y/Y % |

|

20.3% |

|

13.5% |

|

11.8% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Technology & Analytics |

|

$53 |

|

$51 |

|

$67 |

|

12.3% |

Processing & Servicing |

|

18 |

|

21 |

|

25 |

|

16.8% |

G&A |

|

42 |

|

61 |

|

64 |

|

23.3% |

Total |

|

$113 |

|

$133 |

|

$156 |

|

17.2% |

% of Revenue |

|

32.4% |

|

33.5% |

|

35.1% |

|

|

A major culprit of these runaway expenses can be seen in the rapid growth of OnDeck’s headcount. The 475 employees in 2017 quickly became 742 by the end of 2019, a CAGR of 25%. As a result, OnDeck’s revenue per head went from $738,000 in 2017, when the build-up began, to $599,000 in 2019, and will likely fall much further in 2020. While these numbers are slightly better than those of specialty lenders that maintain brick-and-mortar locations (averaging $430,000 per head), they're significantly below those of tech-enabled, pure-play online lenders (more than $1 million per head). It is the latter to which OnDeck must be compared, given its business model.8

By our analysis, which we have shared and reviewed with management, OnDeck could reduce its expenses by more than $50 million, just by bringing its operating expenses as a percent of revenue in line with its online lending peers and returning its headcount to prior levels. To date, OnDeck has announced no expense reductions whatsoever, one of the few companies we own to have failed to take any action.

Who’s on first?

Just what are all of these employees working on? The answer leads us to OnDeck’s companion failure: its lack of strategic focus. As Chairman and CEO Breslow wrote in his March 28, 2020 stockholder letter:

“We entered 2019 with an ambitious agenda focused on building on the success of our US lending franchise, investing in growth adjacencies and innovating on our core risk, technology and funding strengths. We also announced two new strategic priorities for the Company in 2019 – increasing capital efficiency and pursuing a bank charter – and advanced each of these. . . . [W]e are well positioned in 2020 to further expand our core US lending business, scale our international operations to achieve profitability, drive value in our ODX platform [and] advance our effort to obtain a bank charter . . . .”

Ambitious indeed, particularly for a relatively small company. OnDeck is the market leader in online lending to small business, an enormous market ($231 billion in loans less than $250,000), with extensive experience and a differentiated product. This is why we invested in OnDeck in the first place. But what we cannot fathom is why OnDeck seems unwilling or unable to bear down on exploiting this large domestic market opportunity by letting go of its many strategic distractions. In our presentation to management last August, we cautioned that OnDeck suffered from “too many new initiatives, shifting priorities and mixed signals” and urged that “OnDeck should focus on the ‘vital few’ initiatives rather than the ‘useful many.’” Since then, it has not pruned, nor even pared, a single item on its wish-list. Instead, it has continued to fritter away time and money in pursuit of “adjacent” markets, special projects and distant geographies.

By our analysis, OnDeck’s Australian foray has cost stockholders approximately $13 million of losses, plus an unknown sum of capital invested that we estimate approaches $20 million. Harder to measure but costly nonetheless is the distraction of managing a business literally on the other side of the world.9 Admittedly Canada is closer to home, but the Great White North has also been a multi-year financial drain – the magnitude of which we do not know due to hazy disclosure, but is likely similar to Oz, consuming profits, precious capital and valuable time. Management has never satisfied us with its rationales for these adventures, and half-jokingly once commented that at least both countries “speak English.” Sadly, that may be their only nexus to the core US business. OnDeck should immediately exit both of these units, eliminating substantial costs and freeing up needed capital for its domestic business.

The justifications for investments in other areas, such as the “ODX” platform and obtaining a bank charter, seem slightly stronger, but result in a frustratingly similar pattern: consumption of what little profit is available through expense additions, rather than offsetting reductions elsewhere to fund them. ODX is OnDeck’s white-label offering to help banks that struggle to serve small business customers efficiently, but OnDeck struggles to provide ODX efficiently as well. Formerly known as “OnDeck-as-a-Service,” the platform consumed between $5 million and $10 million of total investment prior to 2016 (before any major customer was signed); management identified another $5 to $10 million of annual incremental spend on ODX during 2018 and 2019, but ODX likely contributed to much more of the $42 million expense increase noted earlier than did any other initiative. Much of the expenditure on ODX over the last two years was dedicated to customizing the platform for the use of OnDeck’s then-marquee client, J.P. Morgan (via its Chase Business Bank). But Chase, which has the IT budget to bring such an effort in-house, last year decided to do exactly that, and terminated ODX, which is now in run-off. OnDeck should have been efficiently marketing its ODX offering to smaller regional banks and SBA lenders that are struggling to keep up with behemoths like Chase. They would likely have required less customization.

The pursuit of a bank charter, announced last year, represents the latest of OnDeck’s big projects. Without access to information about the cost, timing or feasibility of this pursuit, it’s difficult for us to analyze its merits. Our fundamental question would be why such a purportedly important initiative cannot be executed with existing resources? We know of many talented individuals in the Company, particularly in legal and government relations areas (and have spoken to a few), yet each year millions of dollars of additional costs are incurred. How many more “investment years” must stockholders endure until the operating leverage we’ve long been promised is actually realized?

Inside baseball

In the same way that OnDeck has been unable to make the transition from its salad days as a tech start-up where profitability didn’t matter, so too its corporate governance has not kept pace with its evolution into a publicly-traded company, with real fiduciary duties owed to the stockholders who now own the Company. In particular, we see many indicia that suggest the Board is neither truly independent nor properly aligned with the interests of the stockholders it is supposed to represent.

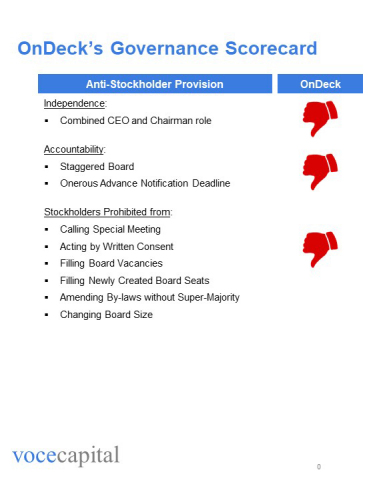

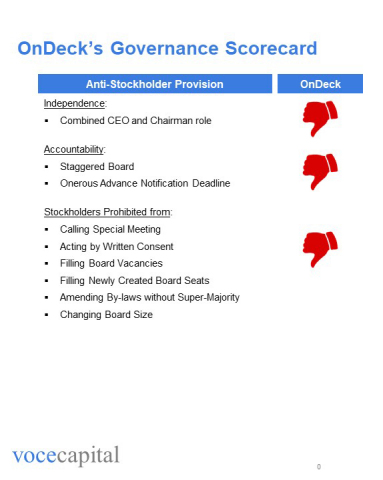

If one were to make a list of the ways in which a Board could structurally insulate itself from accountability or foil any attempt at external influence, OnDeck would almost merit a perfect score. The table (see Figure 1) speaks for itself.

First, OnDeck’s decision to combine the CEO and Board Chairman roles is wrong as a matter of policy and is particularly unwarranted under the circumstances. Best practices are for public company boards to have an independent Chairman, and almost all do. A strong independent Chairman doesn’t just gavel the meetings to order or call the roll. Rather, a Chairman performs an essential role by defining and maintaining the appropriate independence of the Board’s functions from those of management; setting the Board’s agenda and then leading it; and overseeing, on behalf of the entire Board, management and the CEO. In today’s uncharted environment, enterprise risk management is more important than ever, and can only be overseen effectively by a Board with a strong independent Chairman at the helm.

We are aware that OnDeck does have a “Lead Independent Director,” Mr. Henson, with whom we have interacted. However, we concur with the views of proxy advisory firm Glass Lewis that “[w]hile many companies have an independent lead or presiding director who performs many of the same functions of an independent chair (e.g., setting the board meeting agenda), we do not believe this alternate form of independent board leadership provides as robust protection for shareholders as an independent chair.”10

The decision to vest all of this authority with the CEO, Mr. Breslow, is also questionable. Rather than “earning it,” Mr. Breslow was appointed Chairman at the same time he became CEO (at the age of 36), suggesting the Board awarded him the added title as a perquisite rather than due to his experience. While bright and engaging, Mr. Breslow has never sat on another public company board, let alone led one. Nothing indicates that he brings distinguished corporate governance expertise or is somehow uniquely qualified to serve as the Board’s leader to the degree necessary to justify granting him this extraordinary authority. We worry that Mr. Breslow’s outsized role may help explain why the Board has indulged management’s strategic lack of focus, and tolerated its poor performance, for so long.

Second, the Company’s staggered Board offends best governance practices. Directors should stand for election every year. But here’s the irony: In every conversation we’ve had with the Board, it has agreed with us on this point. In fact, we were told that the Board has long pondered de-staggering the Board and considers doing so every year. But that raises a very simple question: Why hasn’t it acted? If it held strong views as to the merits of three-year terms – as misguided as that perspective would be – at least the Board’s resolute commitment to the status quo would be understandable. But to acknowledge a need to fix the issue and yet for several years to have considered it repeatedly but never done it suggests either a lack of candor with us on this point, or utter ineffectiveness in doing its job. Neither answer places the Board in a flattering light.

Third, OnDeck’s advance notification provision for stockholders wishing to nominate Directors (the “Nomination Deadline”) is unreasonably, and uncommonly, onerous. Under Section 2.4(a) of OnDeck’s Amended and Restated Bylaws, effective as of October 31, 2018 (the “ByLaws”), to nominate Directors, stockholders must do so “120 calendar days before the one-year anniversary of the date on which the corporation first mailed its proxy materials.” OnDeck mailed its 2019 Proxy on April 1, 2019, meaning that stockholders wishing to nominate Directors at the 2020 Annual Meeting would have been required to do so by December 3, 2019. How can stockholders be expected to determine whether to seek Board changes prior to receiving the financial report of the previous year; indeed, in OnDeck’s case, the prior year wasn’t even concluded, let alone reported, to stockholders at that time.

120 days prior to mailing of the proxy – itself typically six weeks before the meeting date – effectively gives the Board and management somewhere between five and six months of free reign with little worry that dissatisfied stockholders might react to adverse developments by deciding to nominate Directors to oppose the incumbents. Such an extended period of time is atypical and unacceptable.

But don’t just take our word for it: Look no further than OnDeck’s own past practice, which used to have a Nomination Deadline of 45 days, much more in-line with industry norms. After facing pressure from another vocal, dissatisfied stockholder in 2017, the Board proactively moved to further entrench itself by nearly tripling the length of the notification period. Thus, in October 2018 the Board amended the By-laws to extend the Nomination Deadline from 45 days to the current 120. As a result, the Nomination Deadline was pushed from February 16, 2020 all the way back to December 3, 2019. Such deliberate choices speak volumes about the Board’s true alignment with stockholders and its willingness to be held accountable for its actions. At a minimum, the Board should have allowed stockholders to vote on this ByLaw amendment, rather than acting unilaterally, given the adverse impact it had on stockholder rights.

When taken together – the many structural impediments to stockholder rights, the concentration of power and authority in the CEO and the affirmative entrenchment efforts by the Board – we have serious concerns about the independence, alignment and accountability of OnDeck’s Board to stockholders.

Take me out to the ballgame

The Board’s compensation practices also raise further concerns about its independence, with far too much emphasis on short-term metrics and cash. For example, the short-term incentive plan (“STI”) contains a highly unusual design that is crystalized semi-annually rather than annually. This is way too brief a period to measure or incentivize performance and presents the potential for abuse, as management could game the system through the selection of goals it already knows that it can easily meet. It could also lead to anomalous results where management satisfies one of the half-year periods, barely, and misses the second one, dramatically – and still receives half of the STI, even though the overall annual shortfall is much greater and would have resulted in a lower STI if calculated annually. Yet that’s exactly what happened in 2019.11

The long-term incentive plan (“LTI”), comprised of a variety of restricted stock units, is also excessively short-term in its approach. We were surprised to discover in the 2019 Proxy that the Compensation Committee changed the LTI last year so that awards are earned after only twelve-months, which then vest over the following three years. Prior to 2019, the LTI had three 12-month performance periods, and management had to meet targets during each of those periods in order to be compensated. This unexplained change places undue emphasis on the short-term (only one year, odd for what is supposed to be a long-term incentive plan) and explicitly values “retention” over performance in its vesting design. Interestingly enough, despite calling a portion of this compensation “Performance Units” the amounts are paid out in cash (with no fluctuation in value correlated to stock price) when earned.

We also question the performance targets selected by the Compensation Committee. Each of the plans have a significant component of “Adjusted Pre-Tax Income,” which excludes all stock-based compensation. Why exempt management from the cost of stock it uses to pay employees?12 The LTI is comprised of 40% adjusted gross revenue, with no measure of the quality of it such as credit profile or yield (at least the STI takes into account reserve ratios). What’s also revealing is what’s absent from all of the plans: There’s no component of return on equity, growth of book value nor any per share measure. As such, management has no incentive nor responsibility for the good stewardship of the Company’s equity.

This isn’t the first time we’ve addressed this with OnDeck. Last August, we advised OnDeck that from the perspective of an investor “return on equity is the preferred valuation metric” because “ROE is the most comprehensive and elegant measure of efficiency and financial success, [i]ntegrat[ing] income and balance sheet analysis.” We explicitly recommend it “establish specific GAAP ROE targets for its business then publicly communicate, and commit, to achieving them.” Yet the Compensation Plans ignore ROE altogether.

OnDeck’s plans also fail to align management’s incentives with stockholder interests by relying far too heavily on time-based vesting. The RSUs, when awarded, have no additional performance hurdles; the executive need only remain employed at the Company to ultimately vest. In the case of Mr. Breslow, he gets accelerated vesting on 50% of his units even if he’s terminated without cause. Compounding this misalignment, another concerning change in 2019 was the Compensation Committee’s decision to eliminate stock options altogether and move exclusively to stock-based awards. While a healthy debate can always be had about stock versus options, it matters greatly how they fit into the overall design of the plan. OnDeck’s LTI restricted stock units vest exclusively based on time; no subsequent performance is required thereafter. This purely time-based vesting means that all the executive must do is remain employed at the Company to vest his or her awards. At least with a healthy dose of options in the mix, some inherent performance hurdle accompanies the awards (the stock must at least appreciate above the strike price of the option when granted to have any value).

Finally, the Compensation Committee’s undue generosity has resulted in too rich a mixture of cash in the overall compensation scheme. While the absolute dollars are not outrageous, the steady growth of Mr. Breslow’s salary seems anomalous given the performance of the stock under his tenure. Since the IPO, the Board has nearly doubled his base salary. As a result, over the past three years approximately 54% of Mr. Breslow’s total compensation has been paid in cash.13 Once again, we believe this fails to incentivize long-term performance and does not align executive incentives with those of stockholders.

A schwing and a . . . miss

While the Board has suggested that our requests for change are untimely and inconvenient, the facts don’t support that narrative. As a long-time stockholder we have been constructively engaged with OnDeck for many months over steps we believe that it could take which would protect and unlock stockholder value. As OnDeck began to stumble earlier this year, we escalated this dialogue. On March 13, we presented management with detailed proposals for immediate steps, especially significant cost reductions and a culling of strategic priorities; over a month later, we’ve seen no announcements indicating that any of them have been acted upon. We also requested at that time a meeting with the Board to discuss our strategic and corporate governance concerns, which didn’t occur until ten days later (March 23). On that call, we requested to speak with the Chairs of the Compensation and Nominating and Governance Committees to get answers to questions that we were told could best be obtained from them, which took another two weeks to occur (April 3).

After listening carefully to the Board’s assurances that it had heard our concerns and found many of our ideas to be sensible and already reflected in its thinking, and taking into account what are admittedly challenging circumstances for all involved, the following Monday (April 6) we made one simple proposal: We asked that “the Board include and recommend a proposal at the 2020 Annual Meeting of Stockholders to de-stagger the entire Board immediately so that all Directors will be subject to reelection every year, starting at the 2021 Annual Meeting.” As we explained, our Proposal was tailored to give the “Board and management time and space to act while providing stockholders with an appropriate accountability mechanism, should one become necessary.” In other words, trust but verify. We asked for nothing else to secure our full support at this year’s Annual Meeting.

Consistent with its past practice of considering a Board de-stagger and finding it meritorious while mysteriously failing to actually act upon it, a week later the Board rejected our lone proposal, but not before telling us that it wasn't opposed to it and might do it next year. With all due respect, the letter of talking points we received likely took longer to draft than would have the de-stagger proposal itself. We also reject the suggestion that we dawdled or waited too long to raise our concerns with the Board. OnDeck didn’t even file its proxy until March 18. Many of the concerns we raised in our conversations with the Board, and are reflected in this letter, arose from our review of that document, which had been out for a mere two weeks when we made our proposal. Even today, an entire month remains until the Annual Meeting.

Three strikes

Which brings us full circle. As a result of the Board’s decision to set the advance notification deadline so far in the past, it was impractical for any stockholder to nominate Directors at this year’s Annual Meeting, notwithstanding the strategic blunders and financial crisis engulfing the Company since the start of the year (and pre-COVID). Moreover, the Board’s dogged adherence to its staggered structure where at most three of its members must stand for election each year forces stockholders to not only decide whether to nominate Directors, but when to do so; the years actually matter, because if the terms of the Directors most responsible for the Board’s shortcomings happen to expire in a given year, they will likely buy themselves another three years of protection if they remain unopposed.

Looked at in this way, the 2020 Annual Meeting is indeed a moment in time. The “Class III” Directors who are standing for reelection this year are those that are most directly implicated by the nexus of our concerns about OnDeck’s lack of strategic focus, financial laxity and poor corporate governance:

- Noah Breslow, age 44, Chairman and CEO, and a Director since 2012;

- Jane J. Thompson, age 68, Chairman of Corporate Governance and Nominating Committee, and a Director since 2014; and

- Ronald F. Verni, age 71, Chairman of Compensation Committee (and a member of Corporate Governance and Nominating), and a Director since 2012.

All three of these individuals have been on the Board since prior to the Company’s IPO, and they share a common track record of terrible returns for stockholders as represented by the TSR analysis earlier (all three were also present when the Board voted to unilaterally amend the ByLaws to triple the length of the advance notification deadline after the last run-in with stockholders). They are three of the longest-tenured Directors, but most importantly, they each hold key leadership roles on the Board – as CEO/Chairman and Chair of the two Committees that have most failed stockholders – making them uniquely deserving of responsibility for the Company’s myriad shortcomings. Withholding votes in favor of each of their election this year will be stockholders’ only way of holding them accountable until 2023, given the staggered Board and three-year terms.

Some may ask, “what good does voting ‘no’ do without a competing slate of nominees to replace the incumbents?” Having conducted many proxy contests in the past, Voce inarguably has the wherewithal to nominate and elect directors when given the opportunity. As noted, however, the Board’s unreasonable advance notification deadline has made that impossible this year and the Board has banned all other forms of stockholder action, such as calling a special meeting or acting by written consent.

But one of the few positive aspects of OnDeck’s corporate governance structure is that it contains a “majority voting” standard for uncontested elections such as the one this year (at least for now – one wonders whether the Board will “fix” this provision too with another ByLaw amendment). Even when running unopposed, Directors must receive more votes in favor of their election than withheld or voted against. Directors who do not receive a majority of the votes cast must tender their resignation. In this year’s Proxy, the Board toots its own governance horn for having “a majority vote policy in uncontested director elections and maintain[ing] a director resignation policy.” We fully expect the Board to honor that policy by accepting the resignation of any of the Class III Director who does not obtain a majority of the votes cast. We will seek to hold accountable any continuing Directors that fail to heed the will of stockholders.

Shutout

We therefore urge our fellow stockholders to join us in voting AGAINST all three Class III Directors by withholding votes for them on the Company’s proxy card.

Respectfully yours,

VOCE CAPITAL MANAGEMENT LLC

By: /s/

J. Daniel Plants

Chief Investment Officer

About Voce Capital Management LLC

Voce Capital Management LLC is a fundamental value-oriented, research-driven investment adviser founded in 2011 by J. Daniel Plants. The San Francisco-based firm is 100% employee-owned.

______________________________

1 “OnDeck: An Owner’s Perspective” (August 29, 2019), p.2. We understand our presentation was subsequently shared with the Board.

2 Unless otherwise noted, all prices are as of April 15, 2020. We generally consider February 24, 2020 as the day the markets began to react to the crisis, and use February 21 the “unaffected” price.

3 Peers: CIT Group, Elevate Credit, Enova, LendingClub, Marlin Business Services, OneMain, Regional Management, World Acceptance.

4 Several others have recently made similar comments. KBW: “[W]e are Market Perform [hold] until . . . greater confidence in the path toward higher levels of sustained profitability”; JMP Securities: “Compared to our estimates, operating expenses came in ~8% higher, driving much of the earnings downside.”

5 We focus our analysis on the three-year period from 2017-19. Prior to 2017, a large part of OnDeck’s revenue came from its “marketplace” lending platform, with a different business model and expense structure than today’s balance sheet lending approach.

6 The sales and marketing expenses for OnDeck’s model are variable and grow with originations as new customers are acquired (but should become more efficient over time as repeat customers increase). As such, we exclude them from our analysis of operating expense efficiency.

7 Operating leverage and expense discipline have long been aspirational, but elusive goals, for OnDeck. “Operating leverage is a differentiating factor inherent within OnDeck’s technology-enabled model.” (4Q16 earnings call); “Hope is, as we go 2 to 3 years out, we’re able to . . . increase our efficiency ratio.” (Conference presentation 11/3/16); and “We have made the strategic decision to shift the company’s near-term focus from growing loans under management to achieving profitability.” (1Q17 earnings call).

8 Specialty lenders with brick-and-mortar infrastructure: America's Car-Mart, CIT Group, Consumer Portfolio Services, OneMain, Regional Management, World Acceptance; Pure-play online lenders: Enova and Elevate.

9 Anyone who has ever tried to coordinate a conference call between New York or San Francisco and Sydney quickly realizes how far away it is. We were disappointed to hear that Mr. Breslow goes Down Under once per year, a journey that consumes more than a full calendar day each way just in transit.

10 See Glass Lewis’ 2020 Proxy Paper Guidelines [link].

11 Using Chairman and CEO Breslow as an example, 1H19 performance missed two of three operating targets and resulted in a 75% STI payout, while 2H19 performance met all three operating targets and resulted in a 100% STI payout; if calculated annually, the magnitude of the 1H19 miss would have driven full year misses for two of the three targets.

12 We repeatedly emphasized this to management in our August presentation. For example: “GAAP ROE is our preferred measure. Excluding SBC from in-period ROE means these costs are completely unaccounted for.” (p.28)

13 Cash includes his salary, non-equity plan compensation and “all other” compensation categories.